Dermatologic Emergencies

- related: Dermatology

- tags: #dermatology

Retiform Purpura

Retiform is a descriptive term for a net-like, branching, or stellate configuration, reflecting the vascular structure of the skin. Purpura refers to the nonblanching dark red or purple color resulting from extravasation of erythrocytes into the skin (Figure 127). Retiform purpura signifies total occlusion of cutaneous arterioles with downstream necrosis and hemorrhage in the watershed area of the vessel. Occlusion of several adjacent vessels may result in purpura and necrosis of body segments (Figure 128), particularly in acral regions (digits, ears, genitals).

Retiform purpura is a description, not a diagnosis, and the cause must be determined to preserve life and limb. Because of their devastating consequences, thrombotic and embolic causes should be considered first. Thrombotic causes can be due to unregulated coagulation such as disseminated intravascular coagulation, thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura, or warfarin- or heparin-induced thrombosis. The heart and large vessels may be sources of emboli as seen with bacterial or marantic endocarditis, atrial myxoma, or cholesterol emboli following an intravascular procedure.

Diagnosis is made by history and examination (Table 26). The evaluation should be directed by the most likely associated disorder. A wide net of testing may be necessary in the critically ill patient without a clearly identified underlying condition. In a stable patient, skin biopsy can further direct the evaluation. Treatment is directed toward the underlying cause.

Erythema Multiforme

Erythema multiforme (EM) minor is an immune-mediated condition that can be recognized by its classic targetoid plaques with characteristic histopathologic features. The sharply defined circinate plaques feature two differently colored concentric rings (pale inner ring, red outer ring) surrounding a pale, dusky, vesiculated or crusted center (Figure 129). These plaques typically appear on the face and acral sites, such as the back of the hands, the arms, legs, or feet. The palms and soles may also be involved. Crops of lesions persist for approximately 7 days and resolve without scarring. Most cases of EM minor are caused by infections, herpes simplex virus 1 and 2 being the most common followed by Mycoplasma pneumoniae, particularly in children. Drug-induced cases of EM minor are less frequent and typically result from NSAIDs, antiepileptic agents, or sulfonamides. Mucosal involvement is rare, but if present, is trivial.

Targetoid lesions of erythema multiforme characterized by two concentric rings (pale inner ring, red outer ring) surrounding a pale or dusky center.

Targetoid lesions of erythema multiforme characterized by two concentric rings (pale inner ring, red outer ring) surrounding a pale or dusky center.

EM major has severe mucosal involvement and systemic symptoms in addition to typical skin findings found in EM minor. Lesions in the mouth blister and become painful erosions. They are often polycyclic and involve the buccal mucosa and lips, where the edges may suggest the concentric rings of EM. The eyes, nasopharynx, and genitals are less commonly affected. Fever and malaise may precede rash, and joint pain and swelling have been described. Internal organ involvement should prompt reconsideration of the diagnosis. Skin biopsy can be helpful when the diagnosis is unclear, and direct immunofluorescence can be used to exclude the possibility of autoimmune blistering disease. EM can recur, and in approximately 70% of patients this is associated with herpes simplex virus infection. These patients may benefit from suppressive antiviral therapy. Antimicrobial therapy is helpful if M. pneumoniae is the trigger of EM. If a drug is implicated, the immediate first step is stopping the drug. Systemic glucocorticoids are highly effective for decreasing inflammation and pain, even when patients have an infectious trigger, and short courses (3-4 weeks) should be considered early in the disease.

Stevens-Johnson Syndrome and Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis

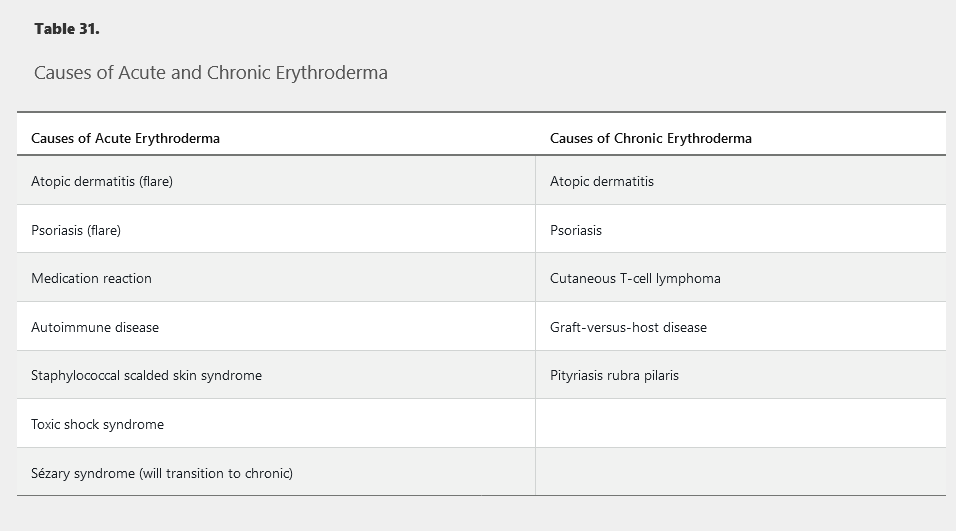

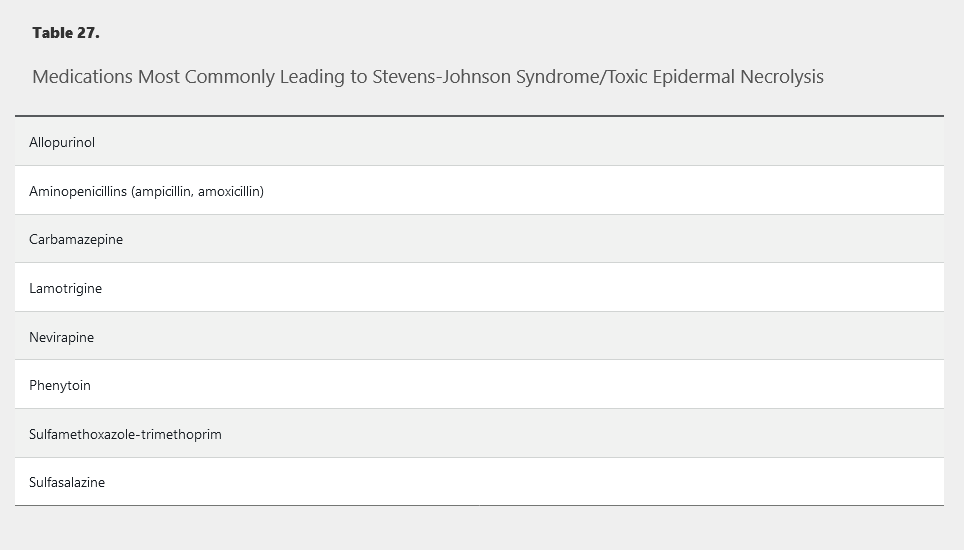

Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS) and toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN) represent a spectrum of severe mucocutaneous reactions defined by the extent of affected body surface area (BSA) involved with blisters and erosions. They are the most severe and deadly of the cutaneous adverse drug reactions. SJS refers to patients with less than 10% BSA affected. Greater than 30% BSA affected is the criterion for TEN. Patients with BSA between 10% and 30% are referred to as SJS/TEN overlap syndrome. Key features include full-thickness epidermal necrosis with involvement of mucous membranes. Essentially all cases of TEN are temporally correlated with medications (Table 27), whereas about 25% of SJS cases are caused by infection or vaccination. HIV infection, kidney disease, uncontrolled autoimmune disease, and human leukocyte antigen type (HLA-B_1502 and HLA-B_5801) also contribute to increased risk. Patients of Asian and South Asian ancestry who are positive for HLA-B_1502 have up to a 10% risk for SJS/TEN when exposed to aromatic anticonvulsants (carbamazepine, phenytoin, and phenobarbital). HLA-B_5801 positivity predicts risk of SJS/TEN upon exposure to allopurinol. The role of genetic screening to prevent these reactions is unsettled.

Symptoms begin usually within 1 to 3 weeks of exposure to the inciting agent. Patients may notice fever, malaise, and symptoms of upper respiratory infections followed by skin pain, grittiness or sand-like irritation of the eyes, and odynophagia. Shortly thereafter, patients develop red or purple dusky macules on the trunk that progress to vesicles, erosion, and ulceration (Figure 130). Painful erosions develop in the mouth, eyes, or genitals in as many as 95% of patients. Unlike EM's predilection for the extremities, SJS and TEN favor the trunk and face. SJS/TEN patients may exhibit atypical targetoid macules demonstrating one or two colored rings, which can be distinguished from the three colored zones of EM. The presence of extensive epidermal sloughing and a positive Nikolsky sign further differentiate SJS/TEN from EM major (Table 28).

Swelling of the lips with vesicles on the lower lip and erosions and mucosal sloughing on the upper lip secondary to Steven-Johnson syndrome.

Swelling of the lips with vesicles on the lower lip and erosions and mucosal sloughing on the upper lip secondary to Steven-Johnson syndrome.

Systemic manifestations are common in SJS/TEN patients. All patients experience fever and malaise. Lymphadenopathy, elevated transaminase levels, and cytopenias are common. Pneumonitis, nephritis, hepatitis, and myocarditis are possible. Hypovolemia and electrolyte imbalances due to loss of the skin barrier are common.

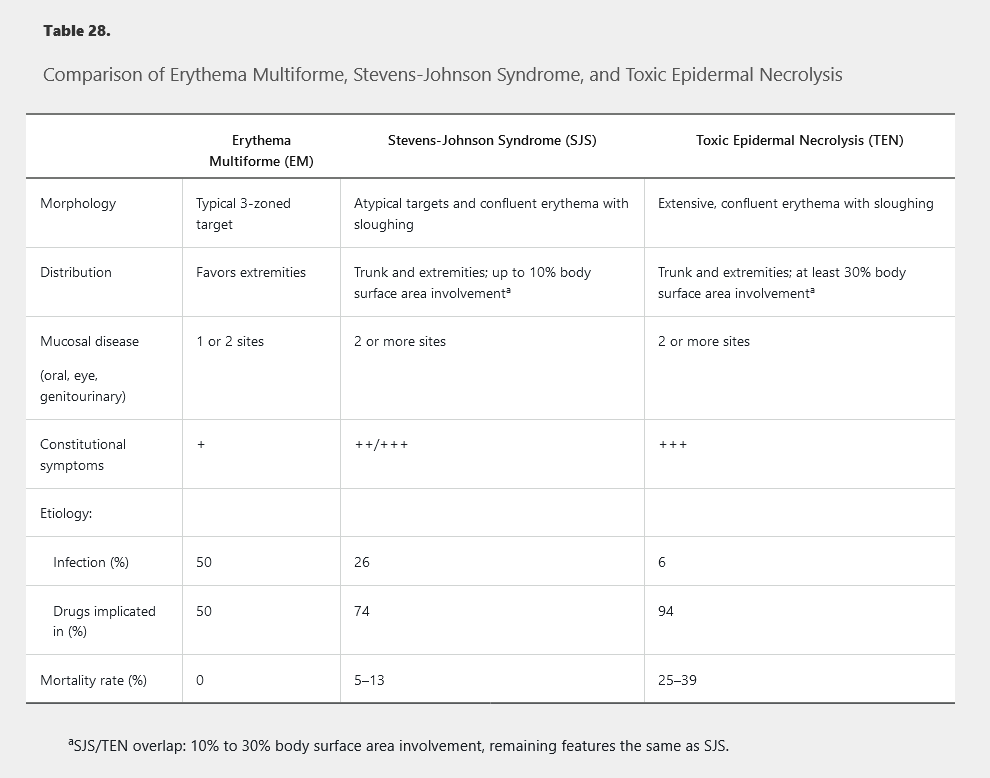

The acute phase of the disease lasts 1 to 2 weeks, and skin reepithelization may take 2 to 4 weeks. Mortality is high with 5% to 10% of SJS cases being fatal and as many as one in three patients with TEN dying from complications related to the disease. Most deaths result from secondary infection, complications of transcutaneous fluid loss, or respiratory distress. Early identification and withdrawal of the causative medication improve outcomes. The SCORTEN scale is a validated, severity-of-illness tool for TEN and SJS that can be applied early in the course of the disease. The mortality rate is directly correlated with the number of SCORTEN variables that are fulfilled (Table 29).

Body surface area is the strongest prognostic indicator in Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrosis (SJS/TEN).

Treatment of SJS/TEN is highly controversial. Intravenous glucocorticoids or intravenous immune globulins are probably the most commonly used treatments, but neither is supported by strong evidence. Supportive care in an ICU with experienced nursing staff is critical for wound care, and many patients are transferred to a burn center. Infection is a significant cause of mortality. A low threshold is recommended for performing cultures and initiation of empiric antibiotics, but use of prophylactic antibiotics is not recommended. Ophthalmologic and urologic consultations are mandatory if ocular or genital involvement is present, as destructive scarring may occur in these areas.

Drug Hypersensitivity Syndrome (or DRESS Syndrome)

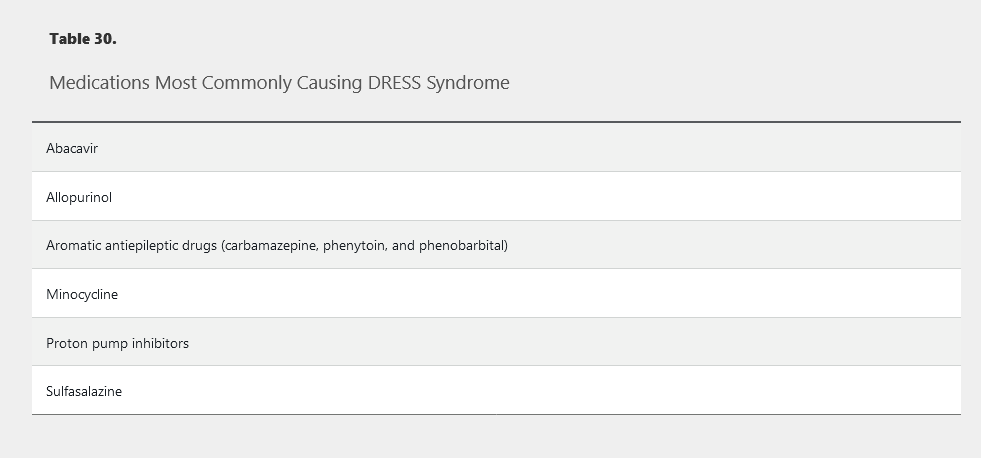

Drug hypersensitivity syndrome (DHS) and drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS) are synonymous and represent another severe life-threatening medication reaction. The most common culprit medications include sulfonamide antibiotics, allopurinol, and anticonvulsants, but many more medications have been implicated (Table 30). Unlike other medication reactions, the onset of symptoms is delayed, often by 2 to 6 weeks, from the time of exposure. Patients begin with fever and flulike symptoms, which are quickly followed by burning skin pain and rash. Patients typically develop a morbilliform exanthem that starts on the face and upper trunk and spreads distally (Figure 131). Eventually the patients develop striking facial edema and redness (SJS/TEN does not have facial edema), a hallmark of this condition. Oral mucosal involvement is common but is less severe than SJS/TEN or EM major.

Generalized morbilliform eruption in a patient with drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS). Vesicles, blisters, and pustules may also be seen.

Generalized morbilliform eruption in a patient with drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS). Vesicles, blisters, and pustules may also be seen.

Systemic involvement is necessary for the diagnosis and most commonly features eosinophilia (SJS does not have eosinophilia) or an atypical lymphocytosis and elevated transaminase levels. Hypotension, shock, and multisystem organ damage are possible, and death occurs in about 10% of patients. Immediate discontinuation of the causative agent is mandatory, and systemic glucocorticoids tapered over weeks to months can be helpful. DRESS caused by an aromatic antiepileptic agent can also pose a serious threat due to cross-reaction with other aromatic antiepileptics. For example, if phenytoin causes DHS but is appropriately stopped, neither phenobarbital nor carbamazepine should be substituted because of the risk of cross-reaction.

Acute Generalized Exanthematous Pustulosis

Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP) refers to the rapid onset of a pustular rash following a medication exposure in a patient without a history of pustular psoriasis. Onset may be as soon as 1 day after exposure to the medication or a few days at most. Patients present with fever, erythema, and eventually develop myriad dense non-folliculocentric pustules, primarily in skin folds and on the trunk (Figure 132). A total of 80% of cases are caused by antibiotics. Most cases are self-limited and resolve within 2 weeks. Treatment consists of cessation of the causative agent and supportive care, but topical and systemic glucocorticoids may be helpful for symptomatic relief. The condition carries a mortality rate of less than 5%.

Erythroderma

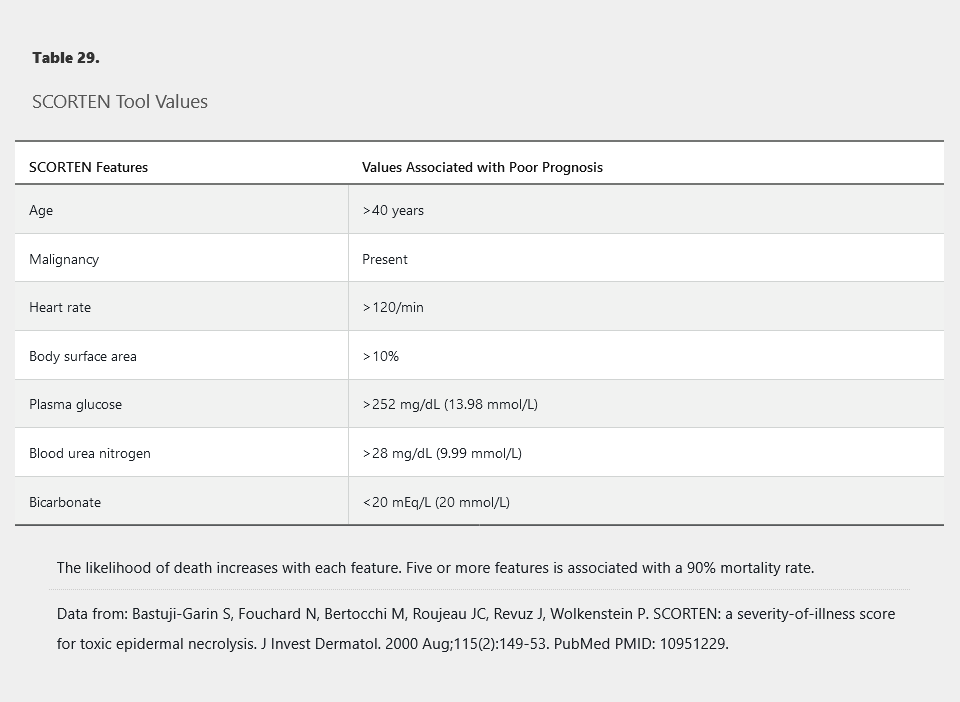

Erythroderma is defined as diffuse erythema covering 80% to 90% body surface area and is commonly associated with pruritus, peripheral edema, erosions, scaling, and lymphadenopathy (Figure 133). The most common causes are idiopathic (up to 40%), exacerbation of a preexisting rash, or medication reaction (Table 31). Atopic dermatitis or psoriasis can flare to erythroderma following injudicious usage and abrupt cessation of systemic glucocorticoids. Alopecia, nail dystrophy, and thickening of the palms and soles are indicative of a long-standing cause such as cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, graft-versus-host disease, psoriasis, or pityriasis rubra pilaris. Drug reactions, staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome, and autoimmune bullous diseases often have a more acute onset without a long-standing history of preceding dermatosis. When erythroderma is acute, thick scaling of the palms and soles or nail changes do not occur. Complications may result from heat and fluid loss across the inflamed skin.

Psoriasis vulgaris can flare to erythroderma following use of systemic glucocorticoids. The most common cause of erythroderma, or redness over 80% body surface area, is a preexisting condition. Peripheral edema, erosions from excoriations due to severe pruritus, and scaling are common findings. Owing to compromise of the skin barrier, affected patients are at risk for dehydration, electrolyte abnormalities, protein loss, heat loss, and infection, which can be fatal. Short courses of systemic glucocorticoids in a patient with psoriasis can result in a striking increase in skin disease upon abrupt cessation. The presence of lamellar scale that bleeds when peeled away (Auspitz sign) and nail pitting support the diagnosis of erythrodermic psoriasis.

Drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS) can also present with erythroderma. This represents a delayed response to a medication several weeks after initiation. Patients present with rash, striking facial edema, peripheral eosinophilia (or less common atypical lymphocytosis), lymphadenopathy, and evidence of organ involvement such as acute kidney injury or abnormal liver chemistry tests.

Management of erythroderma involves treatment of infection and managing fluid and electrolyte imbalance. Emollients will help to restore the skin barrier, and topical glucocorticoids and systemic antihistamines will improve pruritus.

Erythroderma with redness and scaling secondary to pityriasis rubra pilaris.

Erythroderma with redness and scaling secondary to pityriasis rubra pilaris.